#25: Full Moon Party in Cappadocia

Remarkable landscapes, ephemeral friendships, and a party in the hilltops while traveling alone in central Turkey

Above: A farm seen on a hike in Cappadocia (pictures my own)

July 2010

I was sitting with a large group of other backpackers on a restaurant’s patio in a small town in Cappadocia, Turkey. We were finishing our dinner and the sun had nearly finished setting. It was then that we were approached by some young Turkish men working at the restaurant. They told us about a “Full Moon Party” set for that very night in the hilltops. After informing us that it only took place once a year, they suggested with jovial grins that it was a sacred local festival with ancient roots in Anatolian history. There were promises of alcohol, a bonfire, and serene views from the above at night. Another large group of backpackers at a nearby table proclaimed their intention to attend. And although the tourist trap was obvious, we all decided to pile into the Turks’ cars and go with them to the promised party in the mountains.

As dusk was slowly transforming into night, we drove out of town into the early evening. Remnants of the day’s sunlight mixed with the moon beams which shone down upon the valleys, hills, and cliffs of Cappadocia. The road was nearly completely empty save for our caravan of four or five cars, each of them loaded with Turkish men and mixed-gender groups of Western Europeans and North Americans. I relished the realization that I was surrounded by people who had been strangers just a few days before. Those around me were mostly other solo travelers from my hostel. Distinguishing them from my loved ones back home was the fact that, unlike my more permanent friends and relations, these new connections actually knew what part of Turkey I was in at this particular moment. Lacking any kind of consistent Internet or mobile data connection, this was my whole world right now. Surrounded only by those who shared my passion to explore, I was in my element.

I had only planned on staying in Cappadocia for a couple days, but I had soon found myself extending my residence at the hostel until I’d been there for five nights. Tonight, I thought, would probably be my last, although I still had no idea where I’d go the next day. Would I head southeast, toward the Kurdish regions? Would I head north to take in the Black Sea? Or would I head west to Turkey’s Aegean coast? I would decide in the morning. I had at least another three weeks to wander aimlessly around Turkey, at which point I planned on crossing into the Republic of Georgia. But if I really wanted to, then I could stay even longer. And so my indecisiveness was relaxed by the certainty that I wasn’t in a rush. One choice would not preclude another.

Above: Hiking into a Cappadocian valley with some ephemeral friends from the hostel

For now, as we drove up into higher elevations, I thought about the happy memories I had built here with my temporary social group. Aside from Cappadocia’s beauty, it was that tiny community, built from relationships which could hardly be expected to continue very far into the future, that had enticed me to stay longer. Now, near the end, I felt a growing sense of satisfied sadness. I had been traveling alone long enough to realize how rare it was to ever again actually see any of the dozens of memorable and likable people I met… and in this case, I really liked a few of them.

But however intense the connections might seem in those few days when we briefly crossed paths, it was inevitable that eventually we would each return to our origins hundreds or thousands of miles apart from one another. And so although the people back home would know nothing of our experiences beyond what we told them, and although we would only have each other in terms of shared memories of this beautiful place, I was sorrowfully certain that we would shortly revert to being far-flung strangers. The time we had together would seem increasingly fantastical and ancient.

Are they really strangers to me now, over a decade later? Looking back after so many years, my brain easily generates crisp images of their faces, voices, and perspectives, making them all as real to me as a character I’ve imagined for a story. Even though I know this was for a time my genuine reality, it still sometimes seems as if these are minds with whom I once shared some kind of dream. We were doomed, as soon as we each woke up from our joint expedition through the astral plane, to never have any experiences in common again. There would only remain the common recollections and fantasies which, by virtue of the brain’s fallibilities, emotions, and imaginative tendencies, must themselves diverge in detail and feeling over time. We must each mutate into a dim image from the past, contained always somewhere within the neurons and souls of those who for a few special days had been our close adventure companions, and I find that I am grateful for it all even if it was just a dream.

Above: The “Fairy Chimneys” of Cappadocia, the result of volcanic activity and erosion

And Cappadocia certainly was dreamlike. We had spent several days exploring it before we found ourselves piling into cars heading for the mysterious “Full Moon Party.” During that time, we hiked through some of the Earth’s most uniquely structured geological formations, many of them leaving us with a supernatural sense that we were exploring a long-ago terraformed Martian landscape. It was a delusion which I eagerly cultivated as we proceeded on trails flanked by the many so-called fairy chimneys that dot just one of these valleys. While these towers look artificial, they actually come from volcanic activity, although I could hardly blame anyone who comes to perceive a place like Cappadocia as the Creation of the Goddess. Fortunately, the fairy chimneys were only the beginning of the scenery which awaited us during the mornings we spent in awe of our breathtaking surroundings.

In addition to the Mars comparisons, many travelers to Cappadocia say they feel like they have arrived in the homeland of the Flintstones. Local businesses like to play on this with their names, enough that there have been Flintstone cave bars, Flintstone restaurants, Flintstone hostels, and Flintstone travel agencies. And a quick look at the surreal structures in Cappadocian towns makes it easy to appreciate rapid proliferation of such a fun cliché. It is not simply houses and business which have been built directly into the rocks and caves; there is also a huge citadel constructed into the innards of a hilltop - inside of which there once lived a thousand people! There are churches and even small “cities” built in the caves underground. For several millennia, empires as diverse as the Hittites and the Byzantines have taken advantage of Cappadocia’s natural formations to enhance their own defense, building fortresses and other fortifications which are almost indistinguishable from ordinary rock. One can imagine the confusion and terror that would meet those attempting an invasion.

Above: Uçhisar Citadel, a mountain-castle in Cappadocia

Above: With hostel friends inside one of Cappadocia’s many underground cave churches

To Cappadocia’s historic military and religious significance can be added an equestrian tradition stretching across the centuries. Although I did not know the details at the time, and have only come across them through later reading, Cappadocia has a very ancient reputation for its horses. Its community of small stables, which today mostly services tourists, descends from the great imperial ranches of the Eastern Roman Empire. It was this region in modern Turkey which supplied the late East Roman army with many of the horses behind its transformation away from a dependence on infantry and toward a greater reliance on heavy cavalry. Thus Cappadocia was crucial not only for its defensive capacities but also for its resources.

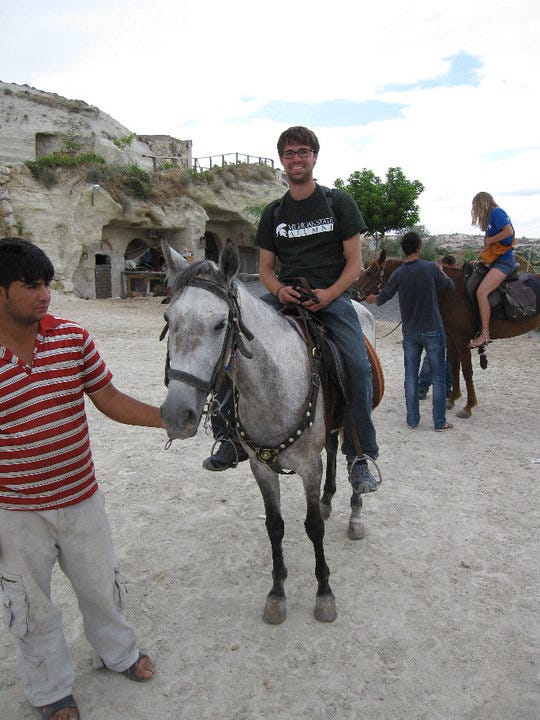

We walked to one of the local ranches so we could ride horses on the trails through the valleys. As for how we used these horses, I am sure my readers will be shocked to discover that I personally lack the necessary skills and mindsets for mounted combat, let alone to even trot. My stint within the storied traditions of Cappadocian equestrianism was therefore limited to sitting happily on my sweet and gentle horsey while the gentle and friendly creature, thankfully far away from any battlefields, walked majestically through the extraordinary hills. Ahead of me and behind me were my similarly skilled friends from the hostel, save for the one who had experience with these wonderful beasts. As we passed through the stunning scenery, each of us celebrated the miracle of Creation which surrounded us.

Above: Me on a horsey, clearly prepared for intense mounted combat

And now, on what was likely to be our final night together, we proceeded higher by car into the mountains, gaining distance with every second from the nearest population center in the valley below. For a while, looking through the window, I could see the glow of human settlements at various locations in the distance. But over time, the lights from the towns sprinkled between the hilltops and cliffs grew ever fainter. Instead, the same glances out the windows revealed only the sides of massive rock formations, each blocking out any light which might reach us from the villages they concealed. Soon, however, we were rejoined with something like civilization. Our car pulled up into the secluded hilltop clearing, flanked on all sides by towers of fairy-chimney rock that obscured most views of the moon.

Above: A local man watches the sunset over Cappadocia

We got out of the vehicle and assessed the somewhat crowded scene before making our way into its center. Young Turkish men rode up on horseback from all directions, and a makeshift stable formed off to the side. Several additional sedans arrived, usually driven by local men but overflowing with mixed-gender backpackers. I assumed the drivers picked these backpackers up, like us, at other hostels and restaurants in the small towns sprinkled around Cappadocia. As we gathered around the growing bonfire, a few men set up a makeshift bar where they sold cheap Turkish beers. Curious about the degree to which a woman’s liberties were tolerated here in what was a relatively conservative part of Turkey, I strained to catch a glimpse of even a minimally feminine presence. And there was, I dimly remember, one woman working for a bit at the bar. But otherwise, the only Turks here were men.

“So I take it,” another backpacker from my car said to the young Turkish man who had driven us, “that the Full Moon Festival isn’t just once per year.”

The Turk laughed. “No, we come here to party all the time,” he said with a happy smile. And then he gestured to the stunning white glow of the beautiful moon, almost fully visible between two rock towers. “We just want to party,” he said with a shrug.

For the next few hours, while periodically buying another beer from the Turks who had set up a bar near the trunk of their car, I shifted between conversations with a group of backpackers from North America, Europe, and Australia. I sat by the fire for a while while an increasingly intoxicated Australian guy told me about all the Turkish women he had apparently banged on the Aegean coast. As for the Turkish men who organized all this, they mostly only came into my vicinity when an American or European woman was with me. But this was frequent enough that their attraction to the flesh of exotic foreigners often fueled a continuous intercultural exchange.

Granted, it was an intercourse that became incoherent as the night advanced. The drinking was heavy and some simply lost command over language. Vibrant abilities to communicate about complex topics dwindled away, replaced by the linguistic ineptitude of a happy intoxication. But my closest companions and I had no more than four or five pilsners. So, eventually, we were an island of tipsy sobriety, seated on the ground at the outer edges of the light from the bonfire. We huddled close together, talking about our travel plans and everything we had done together that week. I knew I was probably leaving Cappadocia the next day, but I didn’t know where I would go.

“Why don’t you come to Ankara?” one of my hostel friends asked. He and a Dutch guy, also part of our little group, were heading together for Turkey’s capital the next day. There, they’d be staying in the apartment of some Turkish art students whom they had met through Couchsurfing. “I’m sure you could crash with them too.”

As I imagined the journeys to come, the fire’s maintenance fell off and it weakened. Turkish men jumped with laughter through the flames. The great moon initiated its exit from the sky, the faintest sunlight began to creep up from the ground in the distance, and local men started to remount their horses and gallop off into the dark.

Above: The fire at the Full Moon Party; on the left, a drunk man jumps over the flames

How, we wondered, would we get back to town? It was a walk of some miles, and the only alternative was piling back into the car with our original driver, as most other backpackers seemed to be doing with theirs. But as our formerly lucid and hospitable host stood before us, assuring us that we just needed to trust him and get into his car, his whole body wobbled back and forth. He spoke in a series of incomplete sentences.

We were five, and four of us decided it would be an act of insanity to get into this man’s car. However far we might be from the town, the unattractive option of walking some two or three hours suddenly seemed like the wisest course.

But what about the fifth? He, the same Australian who had showered me with tales of the Turkish women he encountered on the Aegean, was far drunker than anyone else. He was also visibly exhausted and clearly desperate to get into bed as soon as possible.

“I’m not fucking walking!” he belligerently declared, his movements and eyes indicating a deeply rooted inebriation. He demanded without success that we join him in the car. “You guys are insane!” he said. “How can you walk right now?”

“Yes, yes,” insisted the Turkish guy, struggling to stand straight. “It’s safe, very safe.”

“Are you really not getting in the car?” the Australian asked. “The roads are empty!”

“No way dude, I’m not getting in that car,” I said.

“Me neither,” added another. “You really should walk with us.”

After the Australian’s foolish entreaties had been firmly rejected, he stumbled alone into the passenger seat beside his seemingly black-out drunk chauffeur. We watched the car drive off into the night, carelessly sliding between lanes as it raced with full speed down the hilltops. Following behind as its lights vanished around a bend, and ignoring the offers of other drunks to drive us, we four - two young American men, one young Dutch man, and one young American woman - commenced our tired descent at around three in the morning. As we set forth on the side of a desolate road into the cool and refreshing night, I contemplated the terrifying likelihood that my other companion could die tonight. And I felt relieved that there were others around me who were eager, by walking, to avoid risking his awful fate.

Above: Me with a hostel friend inside one of Cappadocia’s structures built into the rocks

It took us a couple hours to get back into the town, and I cherished every moment with them in the brisk air we breathed. We walked steadily down the shoulder toward the bottom of the mountains. Loving both the late night and the early morning as I do, I could hardly have asked for a more beautiful impromptu hike. Throughout our descent, we were surrounded by the unique shapes of an alien-like landscape. And while my ears savored the sounds of my companions’ friendly voices, my eyes continuously sought glimpses of the mystical formations all around us.

I decided it was okay if we never saw each other again, since none of us was ever going to forget this night, and then I changed my mind, becoming sad about the relationships I must lose. Once our descent from the hilltops was complete, we were down in a large valley. We still couldn’t see our town, and part of me never wanted to arrive there at all. All around us was the colossal emptiness of the cold desert-like plateau. Somewhere in the depths of this dark silence there lingered the shadows of improbably shaped hilltops, cave churches, and mountain fortresses; yet these brief friendships meant so much more to me than any of this scenery ever could.

The sky slowly changed from black to dark blue as we walked, and the desert’s serene quiet was disrupted only occasionally by the passing of semi-trucks or the odd sedan. As we steadily progressed, the horizon displayed increasingly alluring signs that the sun would soon emerge from the other side of the planet. We shifted between happy conversation and private contemplation, and I found myself appreciating the cliffs, slopes, and mysterious outlines which emerged from the earliest phases of twilight. A new day was coming; the future was at hand. We talked about our upcoming travels and the people we had met during the preceding nights in our hostel.

Still undecided about going to Ankara, I had a sense that I would probably never see these people again as long as I lived. Deep breaths of chilly oxygen provided a fragile solace. After the long days we had spent together exploring ancient cave churches, swimming in the pool at the hostel, hiking through valleys that seemed to come from fairy tales, and sharing lazy meals at Cappadocia’s many restaurants, this long walk together through mountains and desert might have been the final significant experience we would ever have in common, and I yearned to simply repeat it all again.

Finally, the light from our town was visible in the distance. Desperate to get into our dorm room beds, we quickened our pace into the emerging morning. At last, we crossed the stark boundary between raw nature and human settlement, walking down the town’s main road until we arrived at our hostel. A profound weariness overtook me as the sun itself finally showed its face, showering us with weak morning rays. A few other guests, just now waking up for early morning hikes, were gathered at a table drinking tea and coffee. These people had only just arrived the day before, and they were already forming the new social groups which would replace our own once we left.

Walking past them and entering my dorm room, I was relieved to see our fifth companion (the one who had gotten into the car) safely asleep in his bed next to mine. There were also a few other people sleeping in beds which had been empty the day before; they must have arrived while we were out. I crawled under my own covers, grateful to finally be able to close my eyes and stop moving. And though I was at first so distracted by the exhaustion in my legs that I could not fall asleep, I soon drifted into dreams about the temporary friendships I had built this week.

Above: One portion of a small town in Cappadocia

I woke up a few hours later, in time for check-out, and headed for the breakfast room.

“Oh my God,” the guy who rode back was saying to a few others. “I have never been more terrified in my entire life than I was on that drive.” Recounting the moment that the car he was in came within a few feet of a head-on collision with a semi-truck, he was noticeably shook, perhaps even lightly traumatized. His voice was cautious and quiet, as if his life were so fragile that even the wrong syllable might end it. I told him I was glad he was still alive, and he told me he was going back to the Aegean.

The hostel was changing. Several familiar faces were departing, and newly arrived strangers were checking in at the front desk. The American and Dutch guys with whom I had walked the night before were heading for the Turkish capital that very afternoon. Inviting me again to tag along, they told me about how cool the mixed-gender group of Turkish art students we’d be staying with were. Nearby, a Turkish hostel worker was adamantly explaining to a guest why the members of some local Islamic sect were “not real Muslims, but blasphemers,” and I craved the opportunity to engage with a more progressive manifestation of Turkish culture. After some deliberation, I decided to join. I grabbed my things, said my goodbyes, and went with my new friends to the station where we boarded a four-hour bus for Ankara.

Related: Border Crossings, Albania to Turkey

Thank you so much for reading! I started The Severed Branch to pursue a project of writing 50 essays in 2022.

Please subscribe to receive my newest writing directly to your e-mail. I truly appreciate your support! Subscriptions, likes, and shares are the best way you can support me.

Thank you!