#27: Plunging into the Kurdish Regions of Southeast Turkey

Warnings leave me nervous about my safety, but I venture anyway to southeast Turkey. In Dogubayazit and Van, I encounter staggering history, enjoy nonstop hospitality, and make cherished connections.

Above: Akdamar Island in Lake Van, Turkey (photos my own)

July 2010

It was at dusk that I arrived by intercity van in the Kurdish city of Dogubayazit near the border with Iran. It was a cramped ride in a three-row vehicle. The middle row lacked three full seats, so a rickety stool had been placed on the van’s carpet near the sliding door instead. Seemingly the only foreigner on board, I was fortunate to be pressed up against the window on a normal seat. Up until now, most of my transportation around Turkey had occurred aboard comfortable and spacious buses departing from coach stations almost as large as airport terminals. The cushiony interiors were usually complete with attendants who served tea and snacks during the ride. But now that I was far to the east in Turkey’s less developed regions, small vans like this would quickly become a normal experience.

After dark, I checked into my hotel and headed up to my room. I opened my backpack and pulled out a big-ass sleeve of digestive biscuits. I ate a dozen for dinner while looking dreamily at the map in my Lonely Planet Turkey Guidebook. On it, I was using a pen to track my progress through Turkey, where I’d now been for over two weeks. I reviewed my route so far: the old imperial capital of Istanbul, the preserved Ottoman town of Safranbolu, the geological wonders of Cappadocia, the art students’ apartment in Ankara, the Black Sea fishing village of Amasra, the Byzantine fortress of Kastamonu, the Greek Orthodox monasteries surrounding Trabzon, and the Kurdish carpet shops of Erzurum.

Despite having visited eight very dispersed locations, I had hardly even enjoyed a fraction of all that Turkey has to entice the traveler. It gave me a rush to think about all that remained to see, learn, and do. With resistance, I resigned myself to the fact I could never experience all of it in the month I had. I thought about the cities to come in my explorations of southeast Turkey, knowing they would be unlike anywhere I’d visited in my life so far. Many were names I’d only seen in books and articles; in most cases, I hadn’t even seen photographs. I was thrilled that I would spend a couple nights in each of them. By pushing myself to venture into a region I’d been warned to avoid, I would dramatically expand my sense for the vast scope of Creation.

Above: The Kurdish-inhabited region of the Middle East (Wikimedia Commons)

But when I was awoken in the middle of the night to what sounded like distant gunfire, I again recalled why this was maybe a bad idea. The very month I was there in southeast Turkey, the PKK - considered a terrorist organization by Turkey, the United States, and the European Union - was intensifying its small-scale assaults upon the Turkish military. Just before my arrival, in fact, these Kurdish militants, in their zeal for independent nationhood, had ended a 14-month ceasefire and killed 80 Turkish soldiers. Now, alone in my hotel room without any digital connection to the outside world, I lay anxiously for a while in the dark hoping that the gun-like sounds would stop. I told myself that it was probably just a construction site.

If not, it was a small blip in a gruesome conflict which had so far killed 40,000 people over the course of the preceding decades. And although the current insurgency was centered not in the cities but in the mountains near the borders with Iraq, where Turkish fighter jets were then running routine airstrikes, my own eyes would soon confirm a heavy Turkish military presence in most municipalities I visited. All of this meant there was always the small risk of being in the wrong place at the wrong time should the insurgents attack in urban areas or even on the highways between them.

I fortified my resolve against this inhibition, always reminding myself that I came from a country where some random psycho could gun me down at any time. My plan was to travel alone around the Kurdish regions, about which I had just written a research paper in my college class and for whose cause I had much sympathy, and that was what I was going to do, official warnings be damned. I reminded myself that the State Department was always too quick with their warnings. After all, my Turkish acquaintance in Trabzon had a military contact, and this officer said the region was mostly safe for traveling. I would be fine if I stuck to the main cities. With these comforting thoughts and the anticipation of discovery, I finally fell back asleep.

Above: Ishak Pasha in Dogubayazit, Turkey

Morning came to Dogubayazit. Mt. Ararat was visible from the terrace on which I took my light breakfast of hard-boiled eggs, olives, and cheese. Its snowy summit towered majestically into the sky far outside the city. There it is, I thought, the final resting place of Noah’s Ark, the ancestral heart of ancient Armenia. At a table nearby, an older white man with a short gray beard and an assortment of gear discussed an upcoming ascent with another man who seemed like a local guide. Together they were charting out some plans on a stack of maps; sometimes they glanced out the window toward the mountain which consumed them. Occasionally eavesdropping on their discussion about the route they were going to take, I wrote for a while in my moleskin to record my reflections from the previous days. I finished my coffee and ate a final piece of cheese. Then I gathered myself to head out and explore Dogubayazit by day.

The first thing I noticed was that there weren’t any women out on the streets. I almost never saw a single woman, covered or not, anywhere in Dogubayazit. The streets seemed flooded with men and boys walking around alone or in groups. The shops were run by men and the taxi drivers were all men. Although the presence of women outdoors had been light in Erzurum, this seemed like another level of seclusion, and I imagined a hundred thousand women confined to their apartments completing exclusively feminine tasks while their husbands walked around drinking beers, smoking cigarettes, and playing backgammon all day. My Trabzon acquaintance had warned me about this part. “You’ll see when you go there,” he had said, “that almost no women are outside, and if they are, they are covered to at least some degree.” He was a Muslim too, but he saw the conservative Islam to the east, should it gain political influence, as a threat to the cosmopolitan ways of the western cities. And he associated this threat not only with the headscarf, which he made clear he despised as a symbol of oppression, but also with Erdogan, Turkey’s current president. In any case, the patriarchy reigned in the streets of Dogubayazit, and the thought of all those women kept inside their homes all day rarely left my mind in southeast Turkey.

My morning in Dogubayazit was very similar to subsequent mornings in other Kurdish cities. As a pale white guy wandering around snapping photos, I always stood out easily. Numerous men and boys approached me in attempts to converse. These interactions played out in bazaars, shops, restaurants, and cafes. As soon as they realized I was an American, they immediately bombarded me with free baklava or tea. Many of them loved America. They saw the United States as a champion of the Kurdish cause thanks to Washington’s military campaigns against the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, a brutal tyrant who had butchered a hundred thousand Kurds.

The French and British imperialists hardly considered the interests of the Kurds when they drew the borders of the modern Middle East in the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916. Each of those mighty colonial powers was far more concerned with dividing between themselves the collapsing Ottoman Empire’s extensive North African and Middle Eastern conquests. It is no surprise, then, that the Kurds never gained a nation-state of their own. Should one emerge in our lifetimes, it would involve one or more regional states losing territory to the new entity.

And to the dread of the implicated national governments, American actions have created increasingly realistic prospects for an independent Kurdistan. After all, America’s 1991 imposition of a no-fly zone over Iraq’s Kurdish regions nurtured new forms of political autonomy for the Iraqi Kurds. And after the American war in Iraq, Iraqi Kurdistan remains a bastion of semi-independence and political autonomy for an ethnic group of 25 million that is regionally concentrated but politically dispersed across Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran. In a 2017 referendum in Iraqi Kurdistan, 92% of voters cast their ballot in favor of independence from Iraq, while the war in Syria has created opportunities for the Kurds there to strengthen fighting capacities. It was often Kurdish soldiers putting up the fiercest resistance against ISIS. It is no wonder that President Erdogan, who fears that Kurdish aspirations toward independence could intensify within Turkey’s own borders, orders military interventions against Kurdish militia in Syria today; these help prevent the Kurds from carving out yet another enduring Kurdish autonomous zone in Syria. Nor is it any surprise that Iraq’s government, aware of the oil fields sprinkled around Iraqi Kurdistan, declines to implement the 2017 referendum. If it is also a growing pride in the Kurdish culture and language which disturbs the enemies of Kurdish statehood, then I found quite a bit to trouble them in southeast Turkey. The Kurds I encountered were excited and eager to share with me their perspectives, customs, and language. Only a handful spoke much English, but this only sparked them to teach me new vocabulary.

Above: The walls of the eighth-century fortress overlooking Van, Turkey

While walking down the street in Dogubayazit that first morning, I was invited by some Kurdish boys to sit down with them at their father’s shop. The father saw me and smiled warmly, urging me to take a seat beside him and his children on one of the stools. Soon another man, summoned by the shop owner, came over with a tray containing numerous glasses of amber tea. “Kurdish tea,” he emphasized to me, although it looked and tasted the same as the Turkish. I smiled and graciously accepted the gift, at which point the tea man went away with the tray. Then the boys, who appeared to be around 13 or 14, began attempting to communicate with me.

Their main goal, when they noticed my small notebook, was to teach me Kurdish words. An older one who spoke some English came over, and I sat there for about an hour while my determined instructors attempted to perfect my faulty pronunciation of their language. It is important to remember that the Kurdish tongue was literally illegal to speak anywhere in Turkey, even in private, between 1980 and 1991. In addition to secularism, the generals who surrounded Mustafa Kemal, founder of modern Turkey, championed the Turkish identity to the point of denying the existence of others. Kurdish culture itself was seen as a threat to Turkish political unity. Many Turkish nationalists even took to calling the Kurds “mountain Turks” while claiming that Kurdish was only a Turkish dialect. Some Turkish leaders, such as the 1930s Foreign Minister Tevfik Rüştü Aras, took it further; the Armenians having been exterminated and deported, these wicked men saw the Kurds as a potential follow-up target who might finally satiate their genocidal tastes. With the awful outlines of this oppressive history in mind, it made me happy to see how proud and pleased the Kurds were to openly embrace their culture and especially their language.

Everywhere I went in southeast Turkey, there was at least one person following me trying to teach me Kurdish and show me the sights. At first I was very nervous about these people approaching me, since many of the men on the streets in more touristy places like Istanbul and Cappadocia will feign friendliness in order to slowly rope the traveler into buying something or paying them as a guide. But here, every time a Kurd approached me, it was to ask me questions, give me baklava, give me tea, give me water, offer me a seat in their shop. If I wanted to interact with locals, all I had to do in the Kurdish cities was stroll through the bazaars, where shop owners competed not to sell me anything but to convince me to sit with them and converse. It was a welcoming friendliness which seemed to spark not just from a habit of hospitality but also from a genuine interest in interacting with someone different. It was easy here to dwell upon the hopelessness of any nationalist project to impose cultural unity in a country like this one, where the modern divides between Kurds and Turks are only the latest in an ancient history of continuous change and immense cultural diversity.

After my morning Kurdish lessons at the shop in Dogubayazit, I hired a taxi off the street and headed just outside town for the other element which makes touring Turkey so special. For anyone interested in world history, planning a trip to Turkey can be overwhelming. The options in Turkey include ancient Greek ruins such as Ephesus and Troy, early Christian cave churches in Cappadocia, and fortresses built nearly a thousand years later by Seljuks and Ottomans. The old heartlands of Armenia are there as well; to the northeast one finds the ruins of Ani, an ancient Armenian capital. To chart the ruins of Turkey is to go back so far in history that I found myself engaged in the fuzziest thoughts about Akkadians, Assyrians, and Hittites. In 2008, a new discovery made the history in Turkey even more staggering. This was Gobekli Tepe in the southeast. It is the oldest known temple in the world, with construction completed an outrageous 12,000 years ago. Involving large stones and intricate carvings, the ruins suggest a level of organization and cooperation among hunter gatherers which was far more complex and developed than previously imagined. Some historians even use Gobekli Tepe as evidence that religion motivated some of the earliest forms of cooperation between scattered small groups and tribes, bringing them together to construct common places of worship. It is is fitting, then, to think about all the deities who have come and gone in this region throughout the millennia ever since: Babylonian and Sumerian gods, Hellenistic gods from the old Greek mythologies, the supreme Zoroastrian god Ahura Mazda, Syrian temples centered upon the worship of the sun, and then of course the Alpha and the Omega: the almighty Abrahamic desert god of the Muslims, Christians, and Jews.

What I saw near Dogubayazit reflected a culture following the most recent of these divinities. The most impressive historical site around that city is Ishak Pasha, an Ottoman palace from the 17th century AD. The fortress is perched up on the summit of a hilltop, with stunning views of Mt. Ararat when the sky is clear. It added new fuel to my interest in the Ottoman Empire, which had first begun when I was traveling in Bosnia. Ever since, I have chastised myself for not knowing enough about them.

But it was in Van, the next Kurdish city I visited, where I first stood in awe of the scale of history. There, shortly after arriving, I explored the ruins of Van Citadel, a stone fortress which overlooks the city and the lake beside it. Van’s fortress is from the eighth century BC, meaning this castle is 2800 years old, built by the rulers of a forgotten kingdom called Urartu. This “Kingdom of Van,” about which historians still know very little, was then integrated into the Achaemenid Persian Empire sometime in the sixth century BC. When it emerged, Persia was both the largest political entity to have ever existed and the first great empire of classical antiquity; it rose and fell three times in a thousand years, taking and losing control or influence over the Van area as its powers expanded and retracted. It was here in these regions, in fact, where the Roman and Persian empires met, clashed, and sometimes cooperated for centuries.

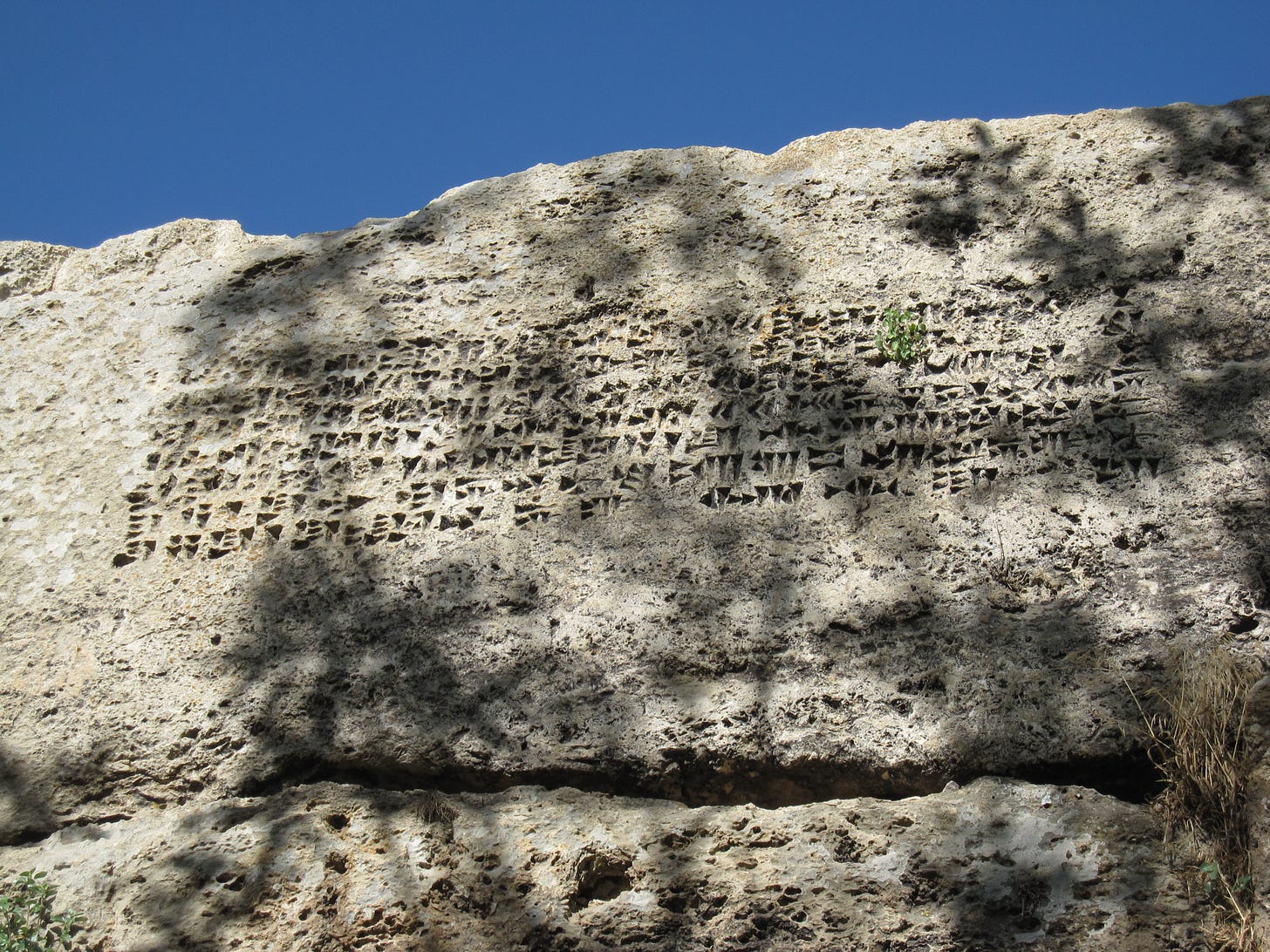

Above: The cuneiform inscription in Van, Turkey

I soon found myself standing before a big rock with writing carved into it using cuneiform script. Invented by the Sumerians in 3500 BC, cuneiform is the oldest writing system currently known to historians. As its impression into the stone wall before me showed, cuneiform writing remained in use two thousand years after its invention. In Van, its wedge-like characters express a proclamation by one of the ancient Persian Empire’s most storied kings: Xerxes I, made particularly famous for his failed invasions of Greece. To this very day, his declaration is repeated in three different extinct languages: old Persian, Babylonian, and Elamite. According to Wikipedia, this 2500-year-old paragraph communicates the following message:

A great god is Ahura Mazda [the supreme Zoroastrian god], the greatest of the gods, who created this earth, who created yonder sky, who created man, created happiness for man, who made Xerxes king, one king of many, one lord of many.

I am Xerxes, the great king, king of kings, king of all kinds of people, king on this earth far and wide, the son of Darius the king, the Achaemenid.

Xerxes the great king proclaims: King Darius, my father, by the favor of Ahura Mazda, made much that is good, and this niche he ordered to be cut; as he did not have an inscription written, then I ordered that this inscription be written.

May Ahura Mazda protect, together with the gods, my kingdom and what I have done.

Still dumbstruck by the cuneiform and the vastness of human history which it suggested to me, I encountered several Iranians who had been let off by a tour bus near the fortress. These were the only other tourists, and several of them spoke English. We laughed when we realized we came from two nations with governments that despised each other. They assured me, without prompting, that they hated Ahmadinejad, Iran’s then-president who had recently rigged an election to stay in power. I laughed and told them I felt the same about Bush. We exchanged some appropriately tentative opinions about Obama. Then we all chuckled and agreed that, as for ordinary Americans and Iranians like us, we could all be friends.

Above: Inside the central mosque in Van. Turkey

Once I returned to Van’s city center, I was still haunted by the thought of the two dozen centuries which had come and gone while that declaration in cuneiform remained. But I was quickly brought back into the present world around me when I found myself wandering around in a beautiful tea garden complete with fountains, flowers, and greenery. Servers walked around with trays of Kurdish tea in the region’s traditional transparent tea glass, offering them to anyone who was sitting on the benches. A group of Kurdish men sitting together spotted me and called me over to them. I approached immediately, and soon we were sitting together in a semi-circle of stone benches beneath a ceiling of brightly colored flora. The server, called by one of my hosts, quickly returned. I gratefully took a hot glass of tea from the tray. I tried to pay him, but he held up a stern hand in refusal.

It soon became clear that none of my new companions spoke even a single word of English. Nevertheless, they had a Turkish to English dictionary which they periodically consulted. Our conversation proceeded through a combination of individual words, markings on the map in my guidebook to describe my travels, and elaborate physical gestures bordering on charades or dances. Soon I made them understand what I had seen so far and what was still to come. Through a combination of primitive and printed communication, they learned about my family, the state of Michigan, and my welcome love for Kurdistan. They told me about their wives and children and the smaller towns around Van where several of them had grown up.

It was only when it came to religion that I lied. This question was asked to me as often in Turkey as “where are you from?” I found that every time I answered it truthfully with “no religion,” my startling words sparked vigorous attempts at my salvation. So I had gotten into the habit of telling people I was a Christian. This declaration, by placing me firmly among the People of the Book, or at least by removing my free agent status, almost never resulted in the dreaded onslaughts of Muslim proselytization which I now strove to avoid. Today, however, although my answer seemed to prevent any attempt to convert me, my new friends decided they wanted to take me with them for the prayers at sunset. After teaching me a game involving trying to slap my wrist with a belt before I could move my hand away, they led me to the central square where the main mosque in town was.

Above: Swimming at Akdamar Island, Lake Van, Turkey

Although I’d sometimes gone inside other mosques during worship, this time I waited patiently in the square outside. Under the shade of a tree, I listened with pleasure to the call to prayer. Its sound had become familiar by now. I had never ceased to savor Allah’s praises when I found myself listening to the beauty of those divinely inspired Arabic verses. I loved especially when I was walking around town, relaxed by a cool evening breeze, and the serene sounds of religion floated musically through the air. It felt that way then, too, while I waited for my new friends to finish their sacred duty.

When the prayer ended, a large crowd emerged from the mosque’s great doors and poured back out into the square. Once we were gathered, my friends invited me to join them inside so I could take a look around, and they even introduced me to the imam. They seemed to tell him that I was an American tourist. Unfortunately, he spoke no more English than I did Turkish or Kurdish, but we both smiled graciously and shook hands. He and the others walked with me along the mosque’s interior walls, happily pointing out elements of its decor with eager and inviting tones. I thanked the imam as best as I could for his hospitality, and he was just able to ask me how I was enjoying Van. I told him I loved it, and he smiled. “Welcome,” he said.

When we walked back out into the fading light, my new friends used finger gestures to indicate a desire to eat. They brought me with them to a stand near the mosque. There they ordered numerous kebabs and Coca-Colas, at which point they invited me to one of their homes. This surprised me, as I had expected to eat with them outside and then walk back to my hotel alone. After briefly imagining what the State Department might say about this new development, I got into a car with a few of them. We drove down the road a while, and then we parked on a secluded street.

Soon I was with them in the large space of a semi-basement. There was a group of about ten of us here, and I watched nervously while one of them tightly closed all the blinds to the windows. Then another started setting newspapers down in the middle of the room. Others scrambled in the kitchen, grabbing cups for the Coca-Cola and plates for the vegetables which they cut up as a side dish. Then we were all sitting in a circle on the floor around the newspapers, eating our kebabs and drinking soda and laughing about nothing. I stayed there for the next three or four hours. There was hardly a moment of silence as we continued using English-Turkish dictionaries to ease communication by speaking with one another in individual words. And there were more resources here, too, specifically pens and pieces of paper and a much larger map of Turkey, all of which assisted in our laborious but joyful communications. We even played several games with rules I was never totally certain about. When it was nearly midnight, a couple of them drove me back to my hotel. There, they asked if I wanted to meet the next day for dinner, and I agreed to see them in the evening.

On that second encounter, there were only four or five of them, and we went to an Internet cafe before sitting down to a meal. Using Google translate on clunky desktops running Windows 98, we were able to take out conversation into the realm of complete sentences. Our haphazard dictionaries, slowly expanding on the papers we carried with us, soon had enough words on them for our conversations in general to become much more effective. At dinner in a restaurant, we began to discuss my plans to leave for Diyarbakir the next morning.

Concerned, they asked me if I had yet visited Akdamar Island on Lake Van. I hadn’t. Although it was one of the top sights in the region, with a tenth-century Armenian church built by an Armenian king who was a vassal of the Abbasid caliphs, the ferry to reach it was a 40-minute drive down the highway. I had seen pictures on the Internet of the church, the island, and the lake, all of it surrounded by mountains and including clear views of Mt. Ararat on the horizon. But I had not been able to find an affordable way to get there. Then they told me they could pick me up early at my hotel, drive me out to the pier for Akdamar, take the ferry with me to the island, have a picnic with me there, and then have me back to the pier in time to catch a bus with onward service to Diyarbakir. I agreed immediately, at which point they went with me to the offices of the bus company just before it closed. The pier for Akdamar was not a routine stop for the bus I would be taking, but my Kurdish friends were able to arrange with the bus people that it would stop there to pick me up in the early afternoon on its way to Diyarbakir. At around eleven at night, they finally dropped me off back at my hotel. We agreed to meet outside the lobby at six in the morning.

The four of them picked me up in the early morning right after I checked out. We swung by a small grocery store to grab an assortment of fruits, snacks, meats, and cheeses. Piling back into the car, where they insisted that I take shotgun, we drove together to Akdamar while blasting Kurdish music from the sedan’s speakers. It was a stunning drive partly along the shores of the lake, and soon we were out on a ferry together just as they promised. They took a few pictures of me on the boat with the Turkish flag behind me on the bow, and we were sure to have a few other Turkish and Kurdish tourists snap some group shots.

Above: The view from the ferry in Lake Van, Turkey

We wandered around on the island for a couple of hours. We gathered along its shores where a few of them took a dive into the water to swim, something I characteristically but politely declined to do. A variety of treats and a few bottles of Coca-Cola were spread out on a blanket which we cast onto the grass near a stupendous viewpoint. From where we ate, we could see the tenth-century Armenian church on one of the island’s various hilltops; Mt. Ararat and the waters of Lake Van glimmered behind it. After we ate and savored the beauty before us, my new friends led me into the ruins of that abandoned Armenian church. Standing by what seemed like an altar, they asked me with genuine curiosity how Christian worship functioned. I tried to explain that I was from a different Christian tradition and that I knew very little about Armenian Christianity. But this proved difficult to communicate, especially when the whole time I just kept thinking guiltily about how I had lied to them about my religion.

After the special morning we spent together, we took the ferry back to the pier. They waited with me on the side of the road for my bus to come. One of them had been given the cell phone number of the driver, whom he called a couple times. Finally we spotted the bus approaching from the distance. Sadness swept over us as the inevitable end of our unexpected connection drew nigh. Each of my new friends took turns hugging me tightly, imploring me to return to Turkey one day. I felt overwhelmed with happiness for what brief moments we shared together, gratitude for their hospitality, and sorrow for our menacing separation. The emotions hit hard and suddenly, as if I didn’t quite realize how much they meant to me until my bus to Diyarbakir was pulling over on the side of the road. I prepared to say goodbye forever.

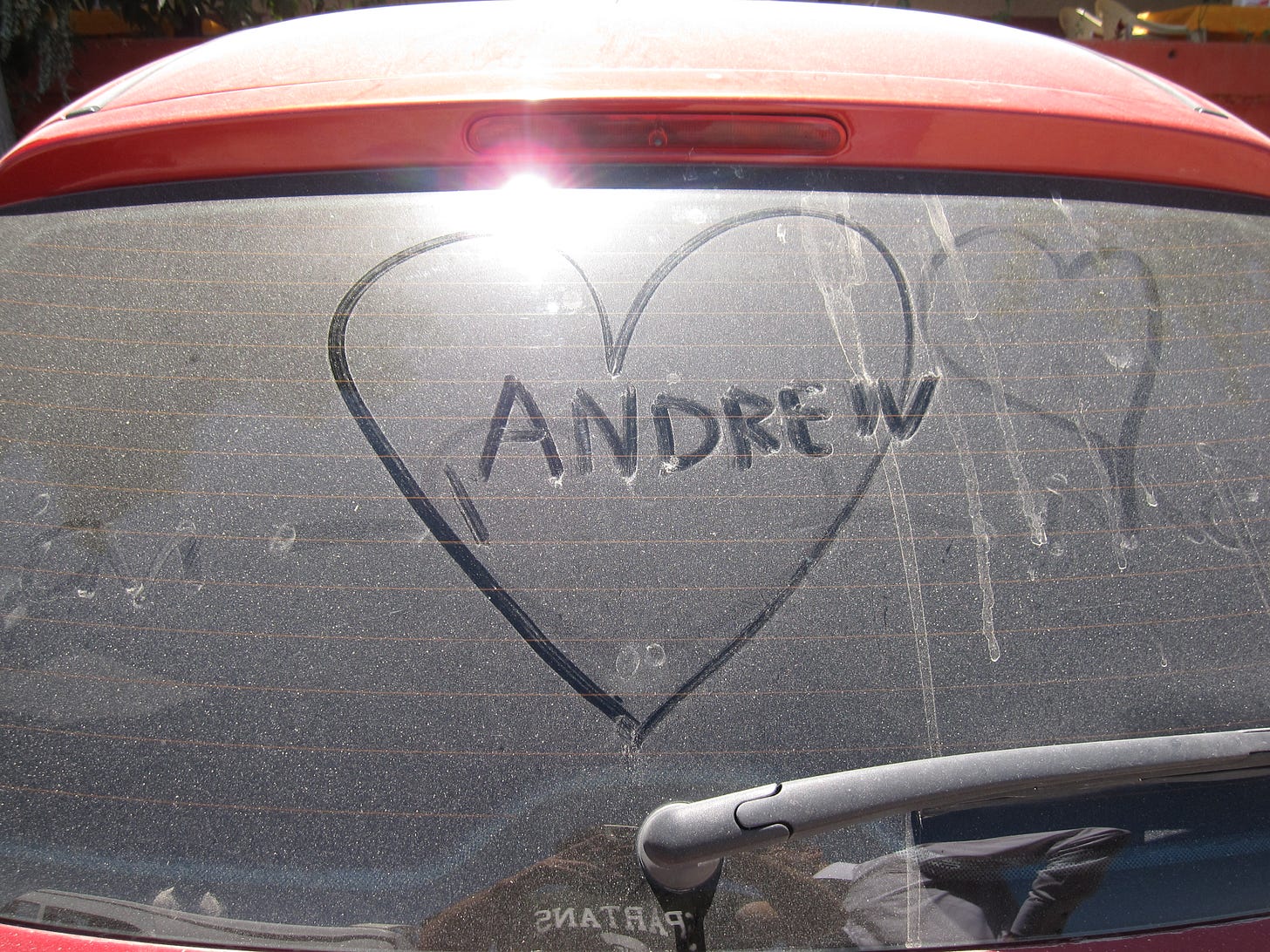

After a final exchange of hugs, my closest friend in the group took his fingers to the dust on the car’s glass. He wrote “Andrew” inside the shape of a heart. “We love you,” he told me, his eyes lightly glistening. “I love you too,” I said. Then I was alone in a seat by the window, waving farewell to them until they dropped out of sight. In five hours, I would arrive after dark at the Kurdish cultural capital of Diyarbakir.

I started The Severed Branch to pursue a project of writing 50 essays in 2022.

Please subscribe to receive my newest writing directly to your e-mail. I truly appreciate your support! Subscriptions, likes, and shares are the best way you can support me.

Thank you!