#8: The Kushan Empire Complicates Cultural Dichotomies

The ancient world of modern Iran, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and India showcases the blurry boundaries and interconnectedness between ancient civilizations

Above: The Kushan Empire 1

I first encountered the ancient world with stories that dealt in stark divisions. First, there were DVD documentaries about Rome’s wars with Carthage. Then, playing Age of Empires in middle school, I led classical civilizations in wars to the death. Later on, when I was a student at Michigan State Spartan football games, the stadium often played the clip from 300 in which Leonidas demands of his soldiers: “Spartans, what is your profession?” Our cringe-inducing answer: “HA-OOH! HA-OOH!”

We were cheering on efforts against the University of Michigan. But the Spartans in 300 were defending their land from an invading Persian army. And the Persians in 300 are an unspeakably wicked, sensual, and luxuriously ornamented crew. With minimal reference to historical reality, the appearance and behavior of these dramatically fictionalized invaders conveys sharp divisions between West and East, Good and Evil.

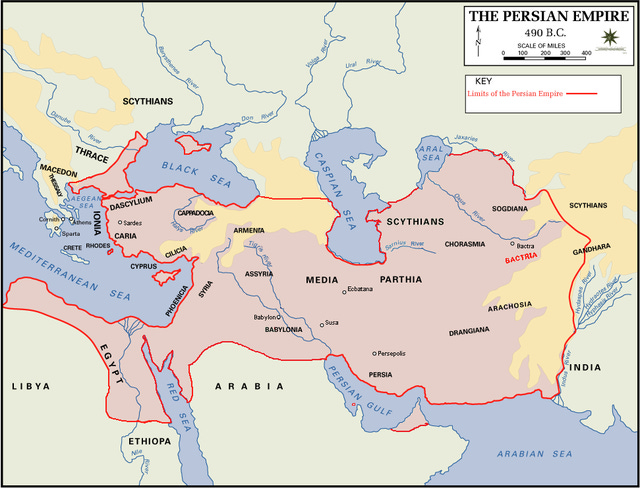

In truth, however, the Persians coming to put an end to the Spartans’ rather grim way of life were the overlords of a culturally diverse and religiously tolerant empire. The Persian army, whose “diversity” in the movie 300 is characterized by the full spectrum of Middle Eastern stereotypes, actually included Greeks from Cyprus and Turkey. Not to mention Egyptians, Lydians, Phoenicians, Sogdians, and Jews.

Above: The Persian Empire in 490 BCE2

As much as they honored the Zoroastrian God Ahura Mazda, Persian rulers strove to earn legitimacy from the various religious and cultural institutions of their subjects. They did so by ceremonially taking the hands of Marduk, god of Babylon, and by acting as Pharaohs in Egypt. It was in this context that many Jews had a compelling rationale for loyalty. Babylon had once conquered Israel, destroyed the Temple in Jerusalem, and forcibly taken the Jews from their land. But once the Persian King Cyrus the Great conquered Babylon, he both allowed the Jews to return to Jerusalem and established the Persian province of Judah. Further encouraging the loyalty of his new subjects, he even decreed the reconstruction of the Temple. For this, he earned repeated appearances in the writings of Jewish prophets in the Bible. But of course, it is now the half-naked Spartan pagans in the movie 300, rather than the Persian kings of ancient Iran, who claim their share in the so-called “Judeo-Christian heritage.”

In terms of fictionalized approaches to conflicts between Greece and Persia, I prefer Gore Vidal’s novel Creation. In it, a Persian diplomat, returning from a lengthy commercial venture to India, is eager to direct the Persian court’s attention to the east rather than to the west. The lands of India are far wealthier than anything we can get from the destitute Greeks, he suggests to King Xerxes. But the Greek exiles, who dominate the Persian court, lobby incessantly for the Persian armies to conquer Greece. They hope the Persians will kill the political rivals who exiled them. Then, as Persian vassals, they can take back their rightful thrones. Persia’s foreign policy remains defined by Greek disputes, resulting in disastrous invasions of Europe.

Just barely within the eastern limits of the Persian empire was a place called Bactria in modern Afghanistan. It held a sacred status in the Zoroastrian religion of ancient Iran. There, most of the people spoke Bactrian, an Eastern Iranian language.

It was in Bactria that the Kushan Empire would have the core of its territory. And the Kushans do even more than the Persians to complicate simplistic cultural divides. Centered upon Afghanistan and Pakistan, but ultimately stretching all the way from Samarkand in Uzbekistan to the Ganges in India, the Kushan Empire is defined by its incredible blending of Greco-Roman, Han Chinese, Iranian, Indian, and nomadic Steppe influences. This was a powerful and deeply multicultural civilization which dominated the center of Eurasia for the first two centuries of the Common Era. But despite its crucial role in the Classical Eurasian economic system, it hardly enters the popular consciousness like Han China or Ancient Rome do. And yet this was among the four major Eurasian superpowers of its time, with immense wealth derived from its facilitation of long-distance trade between Rome, Parthia, India, and China.

For many, Bagram is no doubt associated with the major U.S. airbase in Afghanistan, which American forces abandoned in the summer of 2021. But as historian Craig Benjamin discusses in his excellent book Empires of Ancient Eurasia, Bagram - then a city called Kapisa in Bactria - was one of the capitals of the Kushan Empire. There, in the 1930s, archeologists discovered two ancient storerooms filled with a dizzying variety of luxury goods. These included sculpted ivory and bone from India, expensive silk from China, exquisite stucco ornaments from Greece, and elegant glassware originating from Roman Syria and Egypt. The glass vessels include representations of the great lighthouse in Alexandria and African leopard hunts. At their zenith, the Kushans controlled the port of Barbaricum on the coast of modern Pakistan, through which passed colossal quantities of commerce between China, Arabia, India, and the Roman Empire. The Kushans built much of the land-based infrastructure supporting this trade. And the vast revenues generated by their customs duties certainly helped pay for the powerful armies that maintained control over their massive territory.

But the Kushans were not soulless hoarders of gold and silver. The Kushan emperors patronized the fire temples of the Iranian religion of Zoroastrian. And they easily synthesized religious ideas from multiple traditions. Kushan coins found today in Uzbekistan, Xinjiang, and India depict an eclectic cast of Greek, Iranian, and Indian gods. Religious imagery shifting easily from reign to reign. King Kujula (c. 25 - 80 CE) issued coins with the Greek god Hercules that integrated both Greek and pastoral monarchical symbolism. King Huvishka (c. 152 to c. 190 CE), meanwhile, minted coinage with a known total of twenty-five different gods from Western and Eastern religions. And then came King Vasudeva (c. 192 to c. 225 CE). Likely the son of a South Asian mother, he was named after the Hindu father of Krishna. His coins often show the Indian god Shiva beside his bull Nandi. But as Benjamin points out, Vasudeva’s coins sometimes present Shiva with the name of the Iranian god Oesho. No doubt the Kushan emperors were eager to win legitimacy from their diverse subjects by honoring the many gods in their lands, while also having their own preferences.

The Kushan king with the greatest religious impact must have been the Buddhist King Kanishka (r. 127 - 150 CE). Buddhism had started in India in the sixth century BCE, but it was the Kushan Empire which enabled its rapid spread into China. Benjamin discusses how Chinese diplomats and merchants learned about Buddhism through their involvement in the trade routes that connected China with India via the Kushans. The Kushans built massive stupas around Afghanistan, including one that a Chinese traveler reported to be several hundred feet high. Buddhism flourished across the Kushan Empire as passing merchants made donations to monasteries, and as peaceful trade routes hastened the journeys of missionaries into China. The ruins of some of these Buddhist monasteries, filled with ancient Greco-Buddhist sculptures, have been found near the old Kushan capital of Bagram.

Once Kanishka came to power, he escalated the state’s sponsorship of Buddhism. He constructed monasteries and stupas, even as he continued to honor his Zoroastrian gods on the vast majority of his coins. Benjamin notes that depictions of the Buddha on some of Kanishka’s coins are the first known images ever produced of the Buddha. Kanishka is also credited with having presided over a major council of Buddhist leaders in Kashmir. Kanishka’s efforts ultimately resulted in more standardized and simplified interpretations of his preferred Mahayana Buddhist school, as well as translations of Buddhist Sutras from Gandharan into a more accessible Sanskrit. Both of these developments enhanced the ease with which Mahayana Buddhism, now much more organized, appealed to the population and spread across the region.

Above: The geographic spread of Buddhism3

The Buddhist art which Kanishka encouraged in the Kushan Empire contains fascinating cultural combinations. Sculptors in Kushan-ruled Gandhara (northern Pakistan) created some of the first-ever sculptures of the Buddha. Benjamin describes how Greek, Bactrian, Gandharan, and South Asian artists worked on these together, possibly in workshops controlled by the Kushan monarchs. Given the involvement of Greek craftsmen, as well as the previously mentioned diffusion of decorative Greco-Roman art products into the Kushan Empire, it is no wonder that these early Buddha statues were influenced by then widespread depictions of the Roman Emperor Augustus and the Greek god Apollo.

Interestingly, these Buddhas, which fused influences from India and Europe, were built of a rock called schist. As Benjamin points out, this means that Greek and South Asian craftsmen built these culturally syncretic sculptures out of a material which emerged from the literal collision of the Indo-Australian and Eurasian tectonic plates.

In his book The Roman Empire and the Silk Routes, Raoul McLaughlin discusses how much of this early Buddhist art would ultimately find its way into the Tarim Basin of Central Asia, passage through which connected the Kushan and Chinese empires. Greco-Buddhist art followed the merchants and missionaries traversing these trade routes. This left behind many Greco-Buddhist sculptures throughout the oasis kingdoms on the outer edges of the Taklamakan Desert. Scholars have used these to trace the spread of Buddhism to East Asia.

Benjamin also describes the diverse range of cultural influences on display in Gandharan craftsmen’s secular work, including reliefs depicting the court life of Kushan elites. These reliefs include images of the nomadic clothing which many Kushan rulers would have worn, originating as they did from the Steppe. They also contain Greco-Roman architecture and South Asian symbolism. And the excavated graves of Kushan nobles near Sheberghan in Afghanistan have yielded around 20,000 artifacts displaying a dizzying synthesis of Bactrian, Indian, Chinese, Greek, Roman and nomadic artistic influences.

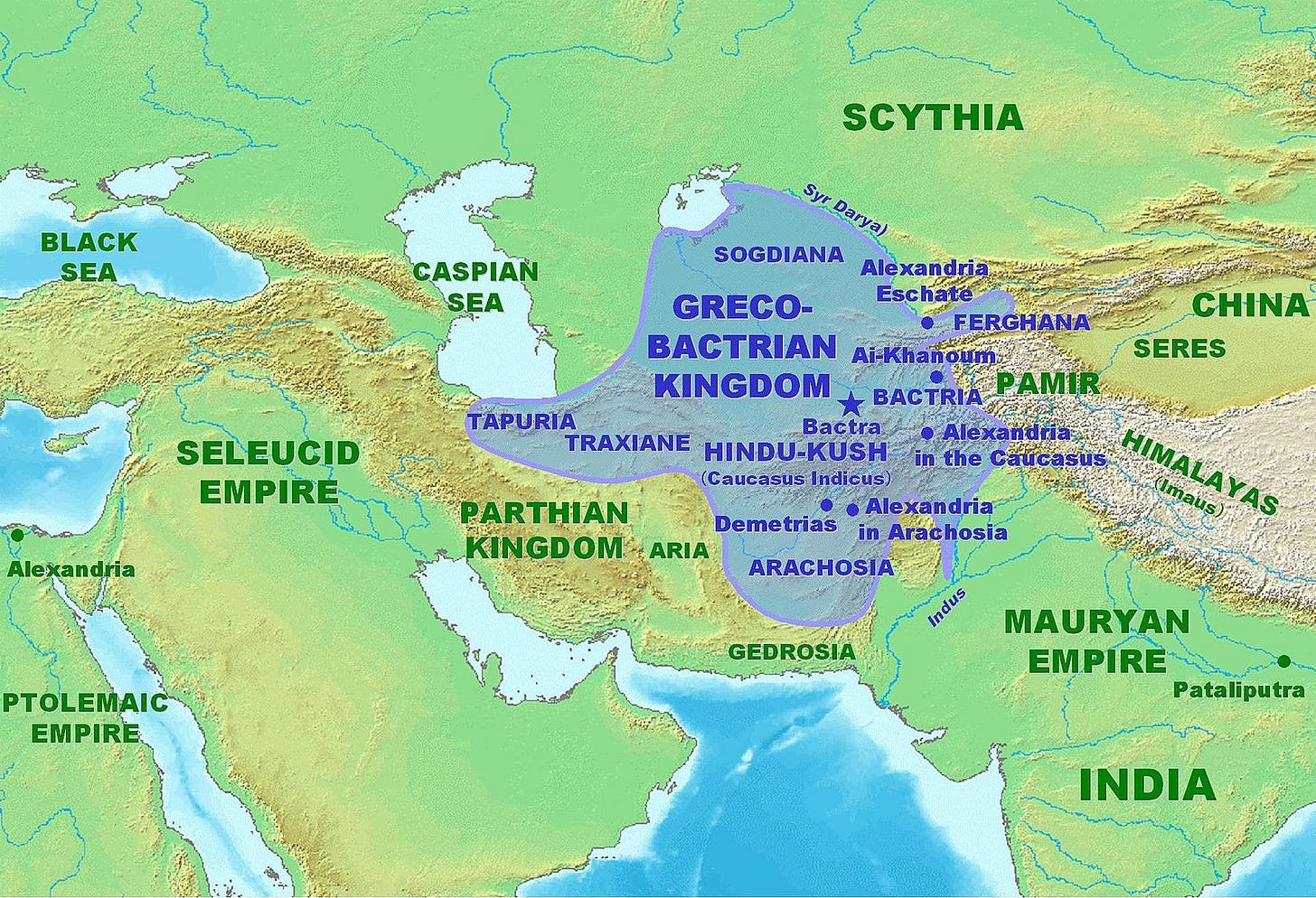

But how is it that such rich collaboration between Greek and South Asian art came to fruition in Pakistan and Afghanistan? Recall the cosmopolitan Achaemenid Persian Empire mentioned earlier, ruled over by the likes of Cyrus, Darius, and Xerxes. Bactria was once a part of that Persian Empire. Until, that is, Alexander the Great’s Greco-Macedonian armies destroyed the Achaemenids and quickly conquered territory stretching from Greece to India. These conquests left behind numerous Greek settlements in modern Afghanistan. By 250 BCE, those Greek settlements would form an independent Greco-Bactrian kingdom, which ruled not only portions of Afghanistan but also parts of Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, northern India, and eastern Iran. Under pressure from increasingly aggressive pastoral peoples, the Greco-Bactrian kingdom later dissolved into various warring states, including independent Indo-Greek kingdoms in northern India, some of them ruled over by Parthian princes who adopted Greek names and titles.

Above: The Greco-Macedonian Empire of Alexander, 323 BCE 4

Above: The Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, 170 BCE 5

Kushan origins can be traced to when the Yuezhi conquered this disunified Greek, Indian, Bactrian, and Iranian hodgepodge. The Yuezhi were a semi-nomadic pastoral people whose original homeland was in Eastern Asia. They migrated to Bactria in order to flee another pastoral group called the Xiongnu (the ancient arch nemeses of China, and possibly the ancestors of the Huns who later terrorized the Romans). Benjamin points out that their initial conquest of Bactria, around 130 BCE, was the first historical event to be commented on by both Chinese and Roman sources, making it a symbolic moment of gradually increasing interconnectedness in a time during which people were first learning about the most distant imaginable lands.

After this initial conquest, however, the Yuezhi remained set in their semi-nomadic pastoral ways, allowing the Greco-Bactrians to more or less govern themselves so long as they paid tribute. These tributes must have been significant, as Bactria already hosted eclectic markets with goods from India, China, and the Mediterranean. This was something which the Chinese explorer who discovered Bactria around the time of the Yuezhis’ conquest was shocked to discover. How, he wondered, had our goods ended up in these markets about which we knew nothing? Suddenly, in an age of discovery, China was aware of great civilizations beyond the world’s known limits. This inspired Chinese emperors to extend their diplomatic and military influence deep into Asia, securing trade routes to what would become the Kushan Empire.

Little is known about the Yuezhi after 130 BCE. Chinese sources claim that they divided into five princedoms scattered throughout Afghanistan. But they were later united under the first Kushan King Kujula. Under Kujula’s military leadership, the newly united Yuezhis conquered the Greco-Bactrians and Indo-Greeks of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. Having transformed themselves into sedentary imperial rulers, they founded the vast Kushan Empire in 25 CE.

Above: The Yuezhi migrations, instigated initially by conflict with the Xiongnu6

Linguistic developments following the Yuezhi conquests display further examples of blurred cultural boundaries. Benjamin points out that the Yuezhi originally spoke the Indo-European language of Tocharian. In the first century of the Kushan Empire, they left Greek as the official language of state in Bactria. But later, perhaps in the interest of trade-links into Iran or easier communication with their subjects, Kanishka changed the language on Kushan coins from Greek to Bactrian in roughly 127 CE.

Perhaps this was the end of Greek’s lengthy time as the official state language in Afghanistan. Yet Greek linguistic and cultural influence remained, partly thanks to the many descendants of earlier Greek settlers, many of whom would work on the first-ever statues of the Buddha. Kanishka’s coins, meanwhile, rendered the Bactrian language in Greek script.

McLaughlin argues that many of the Greek artisans working in the Kushan Empire’s Gandharan workshops of northern Pakistan were not necessarily all descended from Greco-Macedonian settlers. In fact, these could have easily been hired in the ports of India to apply their talents for Kushan patrons. According to the Roman geographer Strabo, 120 merchant ships departed the Roman port of Myos Hormos in Egypt every year to sail across the Indian Ocean and trade in the markets of India. Strabo was writing in the early stages of such trade, suggesting that shipping probably increased beyond this number. One wonders if the Kushans would have had any real conception at all of strict dichotomies between West and East, presiding as they did over a Central Asian realm influenced not only by Greek but also by Roman culture.

Kujula, the founder of the Kushan Empire in (around) 25 CE, was a contemporary of the currently more famous Roman emperors Tiberius, Caligula, Nero, and Vespasian. He depicted himself on his coins with imagery modeled after the first Roman Emperor Augustus, probably since the Kushans had been exposed to the numerous Roman coins which found their way on trade networks into India and Central Asia. McLaughlin suggests that Kujula and his successors would no doubt have rightfully considered their realm to be the Roman Empire’s power equivalent in Central and South Asia. McLaughlin wonders if this might have been on the minds of the Kushan envoys who likely sat with Roman senators for the gladiatorial games held in 107 CE to celebrate the Emperor Trajan’s recent conquest of modern Romania.

The Kushan Empire makes me think about the academic equivalent of the movie 300. In grad school, I subjected myself to the reading of the late Harvard Professor Samuel Huntington’s book The Clash of Civilizations. In it, he argues that global conflicts in the modern world will be shaped by “civilizational fault lines.” He posits strict mental boundaries between what he classifies as Western, Orthodox, Islamic, Hindu, Buddhist, Sinic, and other civilizations. He easily draws lines across maps to predict that the most gruesome conflicts will be found in the regions where these distinct and apparently irreconcilable cultures encounter one another.

Obviously, there are real significant cultural differences between various places in the world, many of them defined by religion. But it is interesting to view the Kushan Empire itself as an ancient civilizational fault line connecting cultures as distant as Greece, India, and China. Yet instead of that multiculturalism generating conflict, the Kushan Empire was internally stable for centuries. It was a multilingual, religiously syncretic, and culturally diverse society. And this was not a weakness but rather a strength, one which produced some of antiquity’s most beautiful art. Its cultural fluidity enabled it to draw upon the talents of merchants, artisans, and thinkers of many languages and traditions, from the Sogdians of Uzbekistan and the Bactrians of Afghanistan to the Greeks and Indians. It easily facilitated trade and enriched itself from the customs duties. And, after its initial conquests and one botched war with China, it was for centuries completely at peace with its nearby rivals, including China and Parthia. Benjamin argues that the Kushans seem to have understood the importance of maintaining peaceful relations with their neighbors so as to safeguard the commercial ties that benefited them all.

In his book, Craig Benjamin discusses frameworks for understanding history which break down old tendencies to view “civilizations” like the Romans, Parthians, Kushans, and Chinese as self-contained and strictly separate units. As Benjamin describes the ancient world of the Silk Roads:

“This regular commingling of states and cultures means that any attempt to consider agrarian civilizations as discrete entities contained within the sort of modern borders we see on maps just doesn’t work. The borders between these various communities were really just vague regions where the control of imperial leaders was regularly contested by the claims of local rulers. These processes were complex and the borders were always fluid.”

The ancient civilizations many of us understand in isolation from one another were deeply interconnected within what Benjamin calls a “world system” or “human web.” He explains that this academic theory developed in the 1970s, before which “civilizations” were the “basic unit for analyzing history on the macro scale.” But we now know that the participation of ancient Eurasian empires in a globalized commercial network stretching from Spain to China means that their fortunes, cultures, and religions cannot be understood in isolation from one another.

Benjamin points out characteristics of globalization as another way of understanding the era of the Kushans. These include “time-space compression,” where long-distance trade that moved products and information across intermediary spaces like the Kushan Empire made the world feel smaller than it ever had before. Similarly, there were processes of “standardization,” with similar approaches to customs duties, taxes, and even currency exchanges based on the gold content of ubiquitous Roman coins.

These globalizing forces mean that the Kushan Empire, as well as trade across the Indian Ocean, had profound legacies for both China and Europe. It was already mentioned that the Kushans were key facilitators of the spread of Buddhism into China. Simultaneously, however, the political stability and transportation infrastructure which the Kushans created enabled the export of Chinese products to evermore distant places. This cultivated the international market for Chinese silk, enabling merchants to more easily satisfy the rapidly growing demand for silk by wealthy Roman elites while also greatly enriching Han China.

Patterns of international trade greatly impacted Roman culture. Roman fashion was transformed by the widespread import of Chinese silk, the trade of which was greatly eased by the Central Asian political stability provided by the Kushans. Gender norms and sexual morality were disrupted as well. Several Roman writers complained about women wearing transparent silk clothing that revealed their bodies. Suddenly, one complained, husbands had lost their exclusive claim to the sight of their wife’s flesh. Yet this moralizing did not put an end to demand. Soon, writers were also criticizing the men who wore silk. This, they suggested, was an effeminate and unmanly dress. Even Roman food evolved thanks to the purchase of ingredients from India, and some Roman religious rituals began integrating incense from distant countries.

Toward the other side of Eurasia, meanwhile, flowed immense amounts of Roman gold and silver, mined in places like Spain and Romania, which clogged the coffers of rulers in Central Asia and India. Not to mention fine Roman glass work, which McLaughlin points out was renowned across much of Asia.

Above: Ancient trade routes across the Indian Ocean7

What about the impact on India? Interestingly, Italian wine was a major Roman export to India. Like Roman glass, much of this arrived via Indian port of Barygaza, with onward shipping southward to the modern Indian state of Kerala as well as northward to the Kushan-controlled port of Barbaricum. Greco-Roman merchants also found themselves in the southern Indian port of Muziris in Kerala. Benjamin notes that both Muziris and Barygaza imported gold, silver, wine, and glass, while the ships returning to Roman Egypt brought with them Indian ivory, agate, and pepper.

But people and ideas were on the move as well. Recall the 120 ships departing annually from Roman Egypt to India. One of those ships is believed by many Christians to have transported the Apostle Thomas. Legend has it that he set sail for India with a group of Greek craftsmen seeking work abroad. He is credited by Christians with having founded a small Christian community in the modern Indian state of Kerala. Those Christians were cut off from the rest of the Christian world for almost a thousand years, until they were found in the 1400s by Portuguese sailors who must have been completely shocked. Portuguese monks informed the Indians that they were going to Hell for following a slightly different version of the faith.

The specifics of St. Thomas’s adventures may not be true, but there is no doubt that Christianity spread across the ocean from the Roman Empire into India. The story of St. Thomas demonstrates the frequent movement of people, goods, and ideas like Christianity, all of which was facilitated by the Indian Ocean’s predictable monsoon winds and the regional stability nurtured by the Kushans. In fact, according to Benjamin, most Silk Road trade did not reach Rome overland via Parthia. Given the frequent wars fought between the Romans and Parthians, as well as high customs duties enacted by Parthia, merchants avoided this route. Instead, they transported goods southward across Kushan territory to Indian ports to then be shipped to Egypt.

It was also via these ship routes that Tamil sailors and merchants came to build communities in Roman Egypt. Benjamin discusses the evidence for this in the ruins of the Roman ports. These include inscriptions in Tamil script, high-quality manufactured goods like cooking utensils that were exported to the Roman Empire from India, and even the remains of houses built from South Asian teak wood. One theory which Benjamin cites is that Tamils settling in Roman Egypt may have broken down their ships and used the wood to build housing. In addition to cooking utensils, these Tamil merchants trafficked in coconuts, precious stones, and peppercorns.

The Roman military’s strength rested partly upon the taxes on trade which was facilitated by Tamil merchants and Kushan stability. According to Andrew Wilson in The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Economy, Roman customs duties at Red Sea ports were so high that they might have covered up to a third of the entire Roman military budget. Further demonstrating the extreme scale of this trade, Wilson observes that Indian pepper was imported in such massive quantities that even non-elites as far north as Britain could afford it.

With the Kushans and the monsoon winds facilitating such unprecedented levels of inter-civilizational dependency and exchange, Benjamin observes that it is not surprising that all four of these superpowers - Han Chinese, Kushan, Parthian, and Roman - entered either collapse or crisis nearly simultaneously in the third century. The Roman Empire alone survived these cataclysms, but only after some fifty years of political disintegration, economic challenges, and civil war. Benjamin uses those events to illustrate the final characteristic of globalization: “vulnerability.”

Above: The Kushan Empire at the center of Eurasia 8

Benjamin argues that the same trade networks which had so enriched all these empires may themselves have hastened this trans-Eurasian collapse. The roads, trails, and seas which took Christian sects deep into China and Buddhist missionaries into the Roman Empire also spread infectious diseases. It was from 165 - 180 CE that the Roman Empire suffered the unidentified “Antonine plague,” which might have been Ebola, small pox, or yellow fever, and which resulted in 2,000 deaths per day just in the city of Rome, for an eventual death rate of 10 percent across the empire. Almost simultaneously, a similar disease broke out in Han China from 151 - 185 CE. Far worse for the Romans was the later “Plague of Cyprian,” which struck from 250 - 270 CE, killing 5,000 people per day in the city of Rome, while devastating the army and labor force. This is believed to have been either Ebola or yellow fever, and it seems to have originated in Ethiopia. It contributed to a breakdown of the cosmopolitan religious tolerance that characterized the time. This is due to it being blamed on Christians, who were seen as having displeased the traditional gods. In any case, there was widespread loss of population across all of Eurasia from such disease outbreaks.

This great era of globalization came to an end with the Kushans, who were overrun by Sassanian invaders in the early third century. And the breakup of the Kushans, along with the Parthians, was unsurprisingly concurrent with the violent disintegration of Han China. Conflict in China would have dramatically reduced exports into Kushan territory, as formerly peaceful roads became unsafe and prosperous Chinese trade cities were besieged. The Kushans, whose state had benefited greatly from customs duties on Chinese imports, must have suffered a decline in state revenues necessary for defense. With chaos descending upon the Kushans, whose orderly rule of so much of South and Central Asia had enabled unprecedentedly far-reaching trade, it is easy to imagine a subsequent decline in the imports arriving from India to Roman Egypt’s ports. This surely must have lessened Roman customs revenues. Thus a chain reaction of disease, war, a reduction in trade, and declining tax revenues seems to have spread from the Pacific to the Atlantic in the third century. This is certainly a powerful example of “vulnerability” under globalization. This was as globalized as the ancient economy could get, and the fates of these empires were profoundly interlinked.

As instability ricocheted through the system, many of the transformative exchanges that had enriched these empires and influenced their cultures came to an end. Benjamin observes that The Silk Road would not return until centuries later, when the Tang Dynasty restored order to China and the great Islamic caliphates brought peace and security to Western and Central Asia. This enabled renewed trans-Eurasian trade.

By thinking about this period of antiquity with the Central Asian Kushan Empire and the Indian Ocean placed at the center of the conversation, we can gain a deeper understanding of the fascinating levels of cultural syncretization and economic exchange that characterized the first Silk Roads Era. At least for the upper classes, it must have been a thrilling time to be alive, with access to previously unknown products arriving from countries that in the past had hardly even entered local imaginations. Meanwhile, the Kushan Empire’s long, stable, and peaceful existence is an example of a supposedly dangerous “civilizational fault line” whose extreme diversity was a source of powerful economic, artistic, and religious legacies, rather than a cause for divisions and animosities. We can understand the human world as one of strict divisions between sharply distinct and conflicting cultures if we wish. But we might also take a moment to appreciate the breathtaking intermingling of different traditions within the great Kushan Empire, as well as the exchanges between previously unconnected civilizations which the Kushans facilitated.

I started The Severed Branch to pursue a project of writing 50 long-form essays in 2022 on topics including history, religion, culture, literature, and travel. These are numbered, but do not need to be read in any particular order.

Please subscribe to receive these directly to your e-mail every Saturday morning. I truly appreciate your support! Subscriptions are the best way you can support me!

If you have already subscribed, please consider liking or sharing this post! Thank you!

Similar Essays:

The Roman Empire’s African, Asian, and Illyrian Reality

Ireland’s Imperial and Religious Legacies

Sources:

Craig Benjamin, Empires of Ancient Eurasia

Raoul McLaughlin, The Roman Empire and the Silk Routes

Andrew Wilson, The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Economy

All maps taken from Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credits:

The original uploader was Feedmecereal at English Wikipedia., CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

DHUSMA, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Gunawan Kartapranata, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Generic Mapping Tools, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

No machine-readable author provided. World Imaging assumed (based on copyright claims)., CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

Asia_whole.svg: TeaandcrumpetsYueh-ChihMigrations.jpg: World ImagingFile:MigracionesDeLosYueh-Chih.svg: Rowanwindwhistlertranslation to English, recolouring: Kanguole, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

User:PHGCOM, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

SY, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons